Header Title

Biotech building – from eco-coffins to growing proteins to growing products

From wasteful, destructive building processes to biodegradable, biotech business opportunities

From burial to biotech

At a wake-like family event after my mother’s recent funeral, I promised the few remaining members of my name-clan that I’d put my proverbial affairs in order – it’d be massively difficult for them to deal with all the morbid practicalities in the for-them-foreign country where I live. Inevitably, this led me to considering burial arrangements and everything involved with such disposal procedures.

In line with my atheist proclivities, I happened upon the idea of a “forest burial“. In Denmark, where I now live, this has been permitted since 2008, but it wasn’t until 2018 that the first forest burial site was set up in an area of privately owned forest. Personally, I’d prefer just to get composted, dumped in a cardboard box, or put on a bonfire, but such disposal methods aren’t considered com il faut in a rule-bound society like this. There are bucketloads of sensibilities and cultural traditions involved, as well as the less-discussed sub-text that a lot of different companies and people earn a living from all the many intervening procedures, as well as from the multitude of billable services that can be derived from these.

Human composting

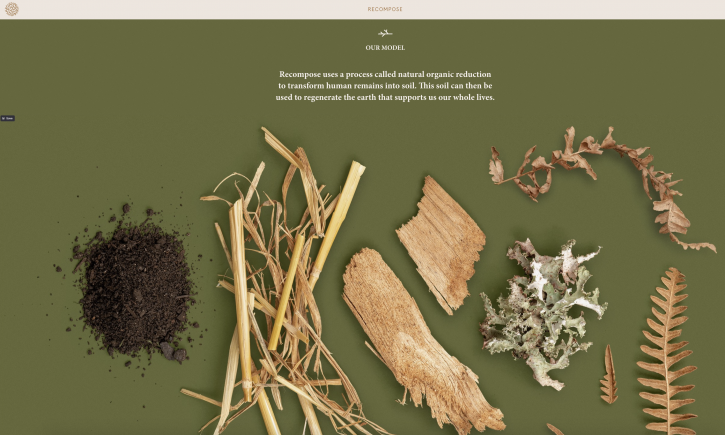

Probably one of the most culturally controversial body disposal strategies is human composting – also known as natural organic reduction. This is usually done in special facilities, with the body placed in a sealed vessel along with selected materials to promote and accelerate the decomposition process. The bodily materials gradually break down – usually over a period of about a month – as a result of natural microbial action, and this is followed by a heating process to minimise any risk of contagion. The resulting “soil” can then be used in a variety of ways, often dependent on a complex mix of cultural norms and regulatory restrictions.

Human composting is apparently legal throughout Sweden, as well as in six US states (as of January 2023). One of the first commercial operators is Recompose, whose website seems to explain the whole concept fairly comprehensively, albeit with a somewhat rosy background shimmer typical for everything even vaguely associated with the undertaking business. Other such companies in the US include Return Home and Earth Funeral Group.

Don’t degenerate or destroy – grow

On the other hand, if burial is the chosen option, and the whole “environmental responsibility” idea is to give meaning, there’s not much point in traditional coffins – biodegradable burial urns are needed to replace conventional environmental burial polluters. So I started investigating such esoteric items …

Producing many of the materials we use to build and operate our society is fundamentally destructive and wasteful. This even applies to coffins, especially if you factor in all their shiny, exotic wooden surfaces, chemically lacquered finishes, and the accompanying inserts, fixtures and fittings. This applies to an exceptional degree in consumer societies where prestige and snobbery kick in for such post-death rituals, and where undertakers/funeral directors/”end of life artists” (or whatever the euphemism currently in fashion may be) have big revenue streams and profit margins to generate, extend and defend.

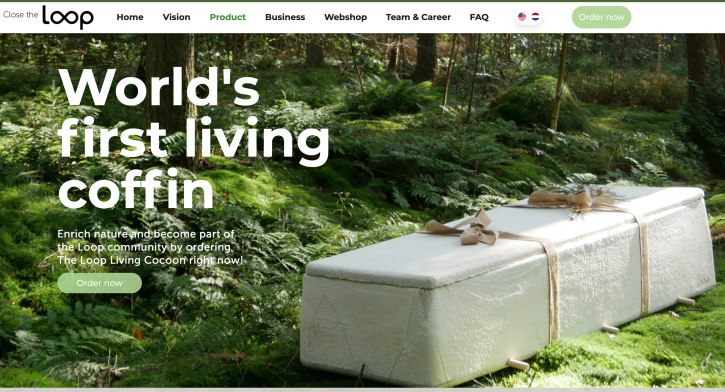

As one possible alternative, I found a Dutch company called Loop Biotech that makes “living” coffins – something you grow, rather than something you manufacture. Loop Biotech promotes a whole “loop of life” concept, and the company wants to remould the world and íts manufacturing processes using ecological structures made of fungal mycelium – the complex fungal network we non-techies and non-growers probably know best as “mushrooms”.

Mycelium is billed as the world’s best recycler, transforming dead organic matter into key nutrients that nature can use to grow new materials and structures. Biomanufactured coffins are thus only one particular iteration of mycelium-based circular economy-based commercial opportunities. Certain parts of the design world have been embracing mycelium since about 2007, when it seems Ecovative in the US first demonstrated home insulation grown on the basis of a patented mushroom-based material, and now licenses its MycoComposite™ technology. Other companies, including Mogu in Italy, Grown in the Netherlands and Biohm in the UK, are also employing mycelium as a material for a wide range of commercial uses. Mycelium composites are now on the market as sustainable replacements for uses as wide-ranging as alternative leather and vegan bacon.

But the really big rethink lies in the basic idea of growing materials and products, rather than manufacturing them from one-time raw materials. as humans have been doing for centuries – or even millennia.

The AI advantage

I’m an ignoramus when it comes to the technical details of biotech et al, but it seems this commercial/scientific playing field is undergoing mega-change, and the number of “components” available for the maker’s palette of building blocks and construction tools is accelerating rapidly.

New-generation development capabilities that stem from (for example) the revolutionary gene engineering and genome editing tools from companies like CRISPR Therapeutics AG and artificial general intelligence (AGI) tools from DeepMind Technologies – a UK-based artificial intelligence subsidiary of Alphabet Inc. – are opening up new vistas for actively working with materials and “components” of organic/biological origin.

As just one mid-2022 example, DeepMind and its AlphaFold algorithms analysed and revealed the structure of 200 million proteins. This process is reported as having predicted the complex 3D shapes and structures of almost every protein known to science – with big implications for discoveries beyond that limited realm.

Non-destructive alternatives?

This whole biotech “revolution” – which some claim will have greater overall change impact than the digital revolution – seems to provide a path away from the centuries-old destructive, emissions-belching manufacturing paradigm to a different set of questions:

- What do you want?

- How do we engineer/tailor (= “grow”) it?