Header Title

Forward-thinking HVAC – engineering marginals or innovative business model?

From technical titillation to on-site realities

Discussions about energy-efficiency ideas often get centred around innovative new technologies, new vehicles, new propulsion systems, new energy sources, etc. Technical innovation is a journo-friendly topic capable of generating sound-bites galore, and often drooled over by pundits and politicos eying easy fixes and sassy slogans.

But the practical realities of business and of users’ real-world purchasing priorities are often very different, and usually start in much more mundane, much more conservative places. In the real world, it’s rare that any exciting new tech gets introduced in a technical or commercial vacuum, or against a “clean sheet” backdrop. There are always existing installations and hardware, as well as the previous-generation mindsets about capabilities and advantages that put them there.

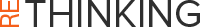

Hardware, money and value

The operating costs and the commercial value of residential, commercial and industrial buildings (particularly in built-up areas) are all-too-often reflections of close-packed machinery spaces in difficult-to-access basements and other decidedly unglamorous equipment spaces, or tucked away (mostly) out of sight on rooftops.

Most owners (and their tenants, whether residential or commercial) have a natural preference for cost reduction and profit margins over environmental credentials and other “soft” parameters. They tend to be less interested in altruistically helping rein in the causes of climate change, and perhaps more interested in commercial drivers that help users toil the effects of climate change.

Old habits die hard

The HVAC world of heating, cooling and air conditioning is a textbook example of this. Technical skills have a natural tendency to dwell on product specs, performance and all the other practical hardware details. Because if these aren’t right, nothing will work.

Unfortunately, this also means the companies that develop, design, manufacture, market and sell this stuff are all-too-often inevitable and involuntary prisoners of their own engineering mindsets, rooted in their own technical specialities. They’re usually working from their own particular supplier perspective and legacy mindsets, often far from the nitty-gritty realities that the customer encounters.

Accommodating differences

In any urban area, industrial estate, technical campus or commercial zone, almost every single building or structure is different. Even seemingly identical building structures (à la modern boxes) often acquire diverging installations as time passes and the functions and processes carried on inside them evolve and change.

Circumstances are also changing outside these buildings, as anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions drive global increases in temperature, and as owners and tenants have to deal with the effects of climate change. To complicate matters still further, many owners (and their tenants) have a natural preference for cost reductions and profit margins over environmental credentials and other “soft” parameters. HVAC decisions aren’t just about hardware any more …

HVAC from the block

Whether in the countryside or in the urban jungles, existing buildings are in the majority – “clean sheet” HVAC installations are only a minuscule minority of any potential market. In Europe, buildings constructed before 1945 represent at least a quarter of the total building stock. What would happen if the urban HVAC business model was instead based on the kaleidoscopic patchworks of messy legacy installations that dominate the real world?

US-based BlocPower provides an interesting example of a refreshing and significant rethink about how to approach HVAC installations and their capabilities – partially reflected in calling itself “a climate technology company”.

According to their website, BlocPower offers building owners smart, all-electric heating, cooling and hot water systems, but without the big burdens of upfront expenditure and investments, based on a purpose-built financial instrument effectively similar to leasing, well described here by TechCrunch. The BlocPower mould-breakers are also on an ambitious electrification mission that features broad-ranging objectives of “climate justice” et al – all adding up to a wide-scoped commercial initiative. The company’s claim is that the use of modern, electrically driven installations (in which air-source heat pumps, water heaters and solar panels figure heavily) weans buildings off using CO2-heavy fossil fuels as well as enabling customers to save 20–40% on annual energy bills.

The key point is actually more the electrification (a path also followed by Futraheat in the UK) than the specifics of the HVAC equipment configuration. if environmental footprint trumps engineering prowess, there is a shift in focus that’ll probably give some traditional HVAC suppliers sleepless nights.

What (apparently) makes this possible is that the company applies proprietary software for the analysis, leasing, project management and monitoring of what it calls “urban clean energy projects”. This presumably means leveraging data from multiple sources to minimise risk, eliminate duplication and streamline project management.

A one-stop-shop for equitable decarbonization, with data-driven efficiency

In 2022, the redoubtable Fast Company magazine ranked BlocPower fourth on its list of the world’s most innovative companies, and the company’s business model seems sufficiently attractive to have a website boaster roster of big-name investors. This is most likely because of the business model behind the actual deliverables …

“Energetic compass”

The kind of energy-profile rating and assessment system presumably at the heart of the BlocPower business model is also available in a somewhat different form from German company Timo Leukefeld GmbH. This

company applies a tool it calls “Energetische Kompass” to develop and provide a comprehensive analysis of any building, with a view to ensuring the maximum possible degree of energy self-sufficiency. The tool apparently includes dynamic simulations that are an effective way to consider different choices and ensure surprise-limited decision-making. The disruptive impact of this works both ways:

- It helps project developers as well as builders to configure workable, cost-able concepts for maximising energy efficiency and minimising the operating costs for any given construction project

- It makes it easier to implement supplier-agnostic planning, along with encouraging independence from energy suppliers and hardware manufacturers as well as the sales strategies of individual trades.

Systemic objectives

The point here is that the HVAC hardware is no longer the real issue. Forward-thinking, energy-responsible HVAC designers, manufacturers and suppliers need to align with (for example) the European Commission Taxonomy Regulation, which lays down specific criteria for whether or not technologies are actually considered “green” and environmentally sustainable. The aim has to be to reach the objectives included in the European Green Deal as well as to meet appropriate EU climate and energy targets for 2030, as well as other internationally mandated measures aimed at achieving net-carbon zero domestic, commercial and business operations by 2050.

HVAC installations are no longer just about equipment and the traditional engineering mindset that produces this hardware. Suppliers traditionally highlight sales successes one site at a time, but we are never going to achieve zero-carbon HVAC ecosystems by considering installations one by one. To achieve mandated macro-targets, the focus has to be on capabilities, and whether/how these capabilities can be scaled up rapidly and cost-effectively.

Scalability via software

When the operating environment (legislative as well as technical and commercial) gets upended as quickly as is already beginning to happen in the face of climate change requirements, it seems unlikely that a business model largely unchanged since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution – the first one! – will continue undisrupted.

The difficulty lies in the practical fact that each building and every configuration is different, and sales usually only address one project or building at a time – a mindset kept in place by traditional silo thinking. This means the “winning card” will probably be in the hands of the companies that can exploit specialist know-how in ways that make it easy to upscale from one to many, and are able to deploy their engineering capabilities at scale, while dialling down the risk and cost involved in systemic changes in HVAC thinking.

Engineering and energy management solutions – in the domestic and commercial HVAC world often featuring air-source heat pump technology and solar panels, which do not require burning off emission-belching fossil fuels – will be prominent at the technical level, but at higher decision-making levels it will probably be algorithms and financial analysis that calls the shots, rather than the traditional HVAC techies. The right software can help decision-makers, buyers and users decide what the end goal is, and the HVAC hardware and its manifold configurations gets relegated to being a mere means to an end.

The legacy manufacturers of HVAC-related equipment may get grandfathered into some forward-thinking installations and may still keep churning out the hardware (the thing they say they’re good at), but at the end of the day such machinery can be purchased by anyone with the nous to apply the technology better and to meet changing needs. If building owners and tenants want results that are in sync with their real-world needs and ESG aspirations, they probably won’t care where the actual hardware comes from. Just consider how many hardware-based businesses have been knocked sideways when their entire manufacturing operations were drastically eroded by global market forces, and gradually became more or less “commoditised”.