Header Title

Plastic – acceptable via understanding, art or toxic capture?

Plastic has rapidly become the elephant in the responsibility room. How can we “relate” to this omnipresent material?

Unfamiliarity breeds ignorance

Plastic has become an omnipresent, integral part of just about every function, item and service in our society. But it’s also a manky material about which most of us know surprisingly little.

I’d challenge most ordinary mortals to explain how plastic is made or moulded – we simply don’t have the same common-sense familiarity that we do with traditional materials such as brick, stone, wood, metal, concrete, fabric, leather, etc. Plastic isn’t something we use in its source form, or something we craft or modify ourselves.

The thing about plastic (in its consumer-facing formats, at least) is that its key selling points usually lie in lightness and thinness – and often in transparency, too, because it’s “just” packaging for the real product treasure inside. The plastic itself rarely gets “seen” or appreciated, and we rarely get a sense of its “structure” or component elements, and there’s certainly no obvious linkage to its grungy, toxic crude oil origins. Plastics (plural …) are an alchemic dark art whose products get delivered to us, or get thrust upon us unseen inside the products and equipment we buy.

And one of the tools in the plastic magician’s toolbox has long been the ability to make plastics of all different types and specs appear to be something other than what they really are. The world’s plastic makers have near-perfected the art of pseudo anything, so it’s hardly surprising that people don’t even know enough about plastic to be able to sort it properly for recycling.

Appreciation and the art of the positive

A Dutch startup is busy rethinking this material anonymity by replacing the art of obfuscation with the art of the positive, in terms of looking at (waste) plastics and seeing beauty as well as commercial potential in their structure.

Rotterdam-based Plasticiet started in the art world, with a passion for sustainable material development. Delving into a visual language inspired by natural stone, the company mostly produces sheet-plastics that look similar to man-made stone composites, like terrazzo. These products have been used in numerous retail stores looking for “something different”, and seeking colour palettes beyond the standard monochrome.

-

The company uses local sources of plastic waste from consumer products, from manufacturing/assembly processes or direct industrial waste. These raw materials are apparently then shredded by specialist suppliers, and then moulded into a 100% recycled plastic sheet material. Plasticiet only uses thermoplastics, which can be melted over and over again. This also does away with any need for a binder component, because the raw material sticks to itself when melted.

Gnarliness becomes a narrative

Plasticiet also ties into the increasingly important waste/responsibility narrative in another key way.

One of the consistently biggest problems for companies that process waste plastics is that the input is often mixed and inconsistent, and often tainted by other materials and other forms of waste. Contaminated, gnarly deliveries of such kinds are usually very difficult to deal with, because they damage machinery, contaminate end products and disrupt effective processing. In such cases, Dutch shredding companies (apparently) contact Plasticiet because the contamination that’s a problem for them might well be a big advantage for Plasticiet – where imperfections and inconsistencies can provide visible structure, depth, narrative and identity. Either by choice or by serendipity.

“Each sheet material in our collection tells a different origin story,” points out Joost Dingemans, co-founder of Plasticiet. “For instance, our Chocolate Factory material is made of discarded moulds from the chocolate industry where the pastel tones are used as colour coding, while Nova mainly contains off-cuts from the production of air cleaning units.”

Such measures can, of course, also provide companies with an easy opportunity to do penance and purchase some kind of symbolic redemption, as well as helping make their ESG credentials an on-display point of discussion.

Plastic from a new perspective

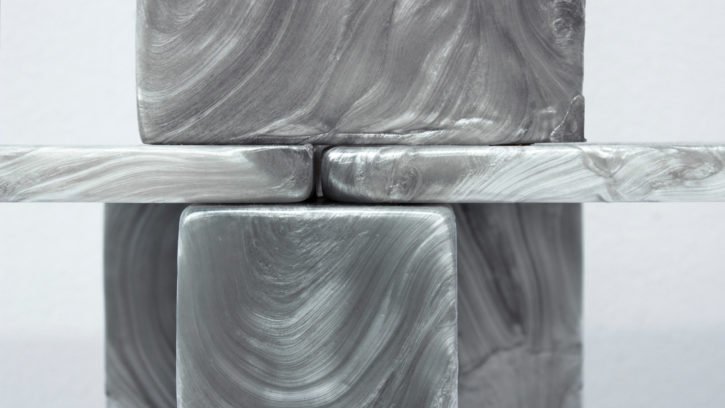

But Plasticiet has now also extended its design scope by presenting its limited-edition Mother of Pearl collection at the March 2020 Collectible design fair in Brussels. This consists of big chunks and slabs of recycled polycarbonate featuring a swirling, shiny finish reminiscent of the eponymous mother of pearl.

This effect is (apparently) created by laboriously kneading, stretching and folding the recycled plastic. This aerates it, and the tiny elongated air bubbles captured within the translucent plastic reflect and refract light, resulting in an iridescent glow with a distinctive effect. And suddenly a big chunk of waste material has structure, depth, tactility and variation. The company reckons this can provide building blocks that can be used for all kinds of purposes, including furniture, building structures and decorative items. And it’ll provide a new/different perception of plastic …

New gold or toxic capture?

The obvious idea behind Plasticiet is that they turn a gnarly waste material into something beautiful – which in the commercial world translates to “sufficiently visually attractive to make people willing to pay more than the production/processing cost for”.

Recycled plastic is rapidly gaining in popularity among designers with a wide range of different motivations. By moving into big, chunky formats that transcend traditional perceptions about plastics, their appearance and their capabilities, the Plasticiet guys have found a way to process large(r) volumes of plastic waste, and turn them back into a desirable material.

But this doesn’t release anyone from the toxic burden of plastic – it just makes a tiny contribution to shifting the day of reckoning a smidgin further out into the future. Essentially, this design/business/product configuration is about toxic capture. But if the art-driven Plasticiet business model helps remove big chunks of the worst, unsorted plastic waste from circulation for a while, it’s at least one tiny additional measure in the millions needed to redress our toxic plastic legacy.