Header Title

Car restoration – peccadillos of the rich or the “right to repair”?

Restoring classic cars – a strange kettle of fish

Classic car collecting and the parallel feeder-vein restoration is a singularly strange phenomenon, with facets reaching out into very different dimensions of human endeavour and ambition. It is a field tugged in a multitude of different directions by many passionate views, as well as powerful commercial interests and well-moneyed egos.

On the one hand, it can (easily) be perceived as toadying to the snob peccadillos of the wealthy – the only people who can really afford to get involved in such a costly, unproductive, non-PC pastime. Restoring old/classic cars can also – or instead – be based on stone-cold bean-counter considerations of value appreciation/investment, sometimes on a par with the pursuit of gemstones, high-end watches or fine wine.

Classic car restoration can also be perceived as a particular branch of technological archaeology/heritage preservation. It can involve a focus on developing/maintaining or even preserving mechanical skills that are becoming increasingly rare in an era of mass production and global supply chains, now often based on digital manufacturing and automation. These precious skills are creative and can restore as well as maintain value as well as beauty, however subjective such perceptions might be.

On the other hand, restoring classic cars can now tie into modern manufacturing and resource management narratives involving the righteous “right to repair” as well as the whole can of worms about disposability, recycling and the longevity of hardware and machinery of all kinds.

Scaling up rare skills

Repairing, resurrecting and restoring old cars involves rare skills. You often only have impartial, broken, corroded, rotten and ancient bits to work with, no immediate blueprint for what to do, and no easy source of replacement items. With some of the real old-timers, it can involve skills and trades that no longer exist, and the process almost always requires bucketloads of specialist manpower, with the individual’s craftsmanship skills at a premium, not least as these experienced seniors gradually decline in numbers. This kind of work is almost always done in small engineering shops, nondescript backyards and back-of-beyond places – usually relatively close to the wealth that’s financing the work.

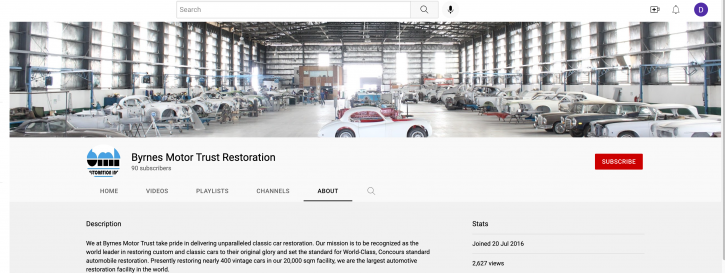

So it’s very difficult to scale up, and especially so in “first world” countries where wages are prohibitively expensive when so mind-bogglingly many man-hours are required. One company with a surprising take on all this is Byrnes Motor Trust Restoration Inc. (a.k.a. BMT) in the Philippines.

Industrialised craftsmanship

Housed in three football-field-sized former aircraft hangars within the old US Air Force Clark Airbase, and extending over an area of more than two hectares, the Byrnes Motor Trust Restoration shop has managed to rethink the business model for classic car restoration. At any given time, they have about 100 cars under dismemberment, with about 150 more sourced and stored ready for their turn under the resuscitation knife.

The BMT business model is, of course, based on a combination of relatively low wages for the relatively high traditional skills available in the Philippines, along with the massive tax/export duties advantages that stem from being located in the Clark Freeport Zone. This particular killer combo is difficult to replicate elsewhere.

In restored cars worth millions (of whatever currency), the quality of the restoration and refurbishment work is crucial for the (perceived) market value of the end product. in this regard, BMT seems to have built up a stellar reputation.

The idea is not entirely unique, however. The Pur Sang setup in Argentina does something similar, tho’ seemingly with more emphasis on ground-up manufacturing work – with everything done in-house. Gorgeous Alfa Romeo and Bugatti replicas seem high on the list, with spectacular old-school one-offs also possible, as here. Restoration icon Jay Leno has a Pur Sang replica of a 1927 Bugatti Type 35 – and raves about it and about what they do.

Both BMT and Pur Sang seem to have managed to find ways to scale up the skills, resources and processes essential if high-quality car restoration is to have a viable commercial future. They are (seemingly) both successful enough not to really need any fancy website to promote their innate wonderfulness. As if website occupancy were any proof of anything in the real world …

Dying breed, dying business?

The ticking bomb under the car restoration business model is that there is (by definition) only a limited number of potential “incoming” projects. It seems the stocks of pre-war vehicles as candidates for restoration have pretty much dried up, and soon there will be fewer cars from the ‘50s to ‘70s that can be worked on. Cars later than that somehow don’t have the same volume or intensity “appeal” to buyers or collectors (though there will always be some outliers and niche nerds). Furthermore, the increasing volumes of plastic and electronics in modern cars – rather than metal and mechanicals – will affect the skill sets needed for restoration, repair and maintenance. As will the take-off of EVs, which do away with most of the traditional mechanical systems. And refurbishing battery packs and electric motors doesn’t have the same artisanal kudos.

Byrnes Motor Trust Restoration Inc. is (allegedly/probably) the largest classic car restorer in the world, so we can be fairly sure they’re perfectly well aware of all this – no teaching grandmothers to suck eggs here.

Right to repair?

The ICE car is no longer a socially acceptable item for veneration, until it gets elevated to collectable art status, and millionaires start drooling big dollops of dollars. At first glance, one might think the Byrnes/Pur Sang business model is engaged in a non-PC dance with the devil, acolytes at the crumbling altar of the internal combustion engine and the havoc that particular technological innovation has wreaked on our society.

But that it is only the objects to which the Byrnes and Pur Sang artisans apply their skills. Couldn’t such remarkable, versatile panel beating, metalworking, electrical and mechanical skills be applied elsewhere where the much-discussed “right to repair” (or even the right to improve) ethos could be implemented?

This would provide a high-impact, viable alternative to the “we don’t fix – we replace” ethos that has dominated so much of our consumer society and then also the value chains used in industry. The redoubtable John Deere company has become the poster child of “access to know-how” evil by trying to limit and deny farmers their traditional “right to repair” their agricultural equipment. The more electronic and the more software it takes to make industrial equipment run, the more companies are tempted to limit access in order to ensure their revenue flows.

The blessings of better-than-new

Artisanal skills encourage, facilitate and support strong sentimental attachments to a car, and bring it back from the automotive graveyard. This paves the way to rescuing a tiny sliver of the world’s automobile production from decay and discard – upcycling and value instead of disposal and waste.

Such capabilities can, of course, also be applied to repairing, refitting and re-engineering classic car designs as better-than-new restomods, upgrades and droolworthy statements of engineering and design appreciation. Examples include Hemmels working on Mercedes Pagodas, re-engineered Jensens, Porsche 911s from Singer, the gorgeous Eagle takes on Jaguar E-Types, and the whole ICON stable of classically patina’ed restomods from Jonathan Ward.

However, almost all of these shops cater primarily to the wishes of the wealthy, and cannot really be scaled up or “democratised” in the Byrnes and Pur Sang manner.

Packaged business capabilities

Nike recently unveiled a robot-augmented in-shop system called Bot Initiated Longevity Lab (= BILL, of course) that uses water-based cleaning products and recycled polyester patches to clean, polish and repair old trainers (well, actually only four specific popular Nike models).

Couldn’t we imagine that the multitude of exceptional hands-on craftsmanship skills available at the Byrnes and Pur Sang plants (and elsewhere, of course) could be similarly configured to extend the useful life of a much wider range of consumer/industrial hardware items with a big metal/mechanical content?

In the world of digital enterprise technologies, the idea about “composable commerce” involves giving organisations the opportunity to pick and choose what Gartner describes as “packaged business capabilities”. One good example of this is the MACH Alliance technology ecosystem based on microservices and software, but also reflecting a manifesto’ed way of thinking about abolishing designed obsolescence. MACH technologies support enterprise structures in which every component is pluggable, scalable and replaceable, and can be continuously improved to meet evolving technical and commercial requirements.

if organised sufficiently well and in accordance with an appropriate business model, this seems part of a big potential for moving a wider swathe of manufacturing processes and capabilities from disposable to usable. Classic cars could be just the beginning.