Header Title

Breaking the bluster barrier about biodegradability

Biodegradability is one of the pivotal definition buzzwords in bioplastics and the whole recycling circle. Polymateria and a new UK standard seem to be nudging perceptions about this

Claims about biodegradability – and what it really means – are big in the world of commercial bioplastics. I do a fair bit of work in this rapidly growing field, and there seem to be a lot of startups making this golden claim, liberally spread over zingy websites and marketing materials. Unfortunately, the path to commercial failure is paved with mere good intentions – and the potholes are particularly prevalent in the well-intentioned “green” space.

I’m not an expert, but even I can see that companies often seem to be making such key claims with very little “meat” or technical information to back it up. Such unsubstantiated assertions may be “fit for purpose” in the media world of journalistic over-simplification and in the narrow-track “green storytelling” industry. But they certainly aren’t sufficient amid the gnarly technical realities of the commercial world, where everything has to be comprehensively tech-spec’ed, exhaustively documented and legally bullet-proof. No one considering adopting a new process or technology for key materials wants to put their career – or even their company’s/employer’s existence – on the line by blithely accepting an unknown supplier’s claims at unquestioned face value.

Claims, definitions, standards and certification

In business, the path forward from PR vagueness, aspirations and assertions often lies in agreed international (or even national) standards. Such agreements about forward-thinking technical standards can go a long way to softening the usual barriers to entry.

Two key sources of developing and establishing such standards are ASTM International, one of the largest voluntary standards development organisations in the world, and the Biodegradable Products Institute. The current state of play about biodegradability standards is something like this, although the standards, benchmarks and milestones are in flux as well as growing in number as the bioplastics industry develops and matures.

- · ASTM D6400: Test to certify whether a product can be composted

- · ASTM D6868: Test to determine whether a biodegradable plastic is truly biodegradable

- · EN 13432:2000 European test to determine the biodegradability of plastics

New expectations to abide by?

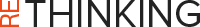

But there’s a new kid in town. According to the new PAS 9017 specification published for public comment by the British Standards Institute in July 2020, any plastic claiming to be biodegradable will have to pass a specific test in order to prove that it breaks down into a harmless wax that does not contain microplastics or nanoplastics. Strictly speaking, this is a PAS (Publicly Available Specification) – a fast-track standardisation document that defines good practice for a product, service or process. It’s not an actual standard, but it is a powerful way to establish the advantages and technical integrity of an innovation or a new approach, as well as a good indication of which way the commercial bioplastics winds are blowing.

Strictly speaking, this is a PAS (Publicly Available Specification) – a fast-track standardisation document that defines good practice for a product, service or process. It’s not an actual standard, but it is a powerful way to establish the advantages and technical integrity of an innovation or a new approach, as well as a good indication of which way the commercial bioplastics winds are blowing.

PAS 9017 is the first stakeholder consensus on how to measure the biodegradability of polyolefins that will accelerate the verification of technologies for plastic biodegradation

Bio-transformation ingredient

The benchmark for the PAS 9017 specification was apparently established in collaboration with Polymateria – a company based at Imperial College, London – and agreed after independent review and discussions with industry stakeholders, waste and recycling groups, and several British government bodies, as is normal practice.

from the Polymateria website

The basic idea seems to be that Polymateria (great name!) bio-transformation chemicals are added to plastic at the manufacturing stage. Featuring a bespoke formula element for each specific type of plastic item, the formula used in production transforms the most common plastic litter items – such as food cartons, cups food films and bottles – into a sludge at a specific, planned time in each product’s life. According to the company, once the breakdown of the product begins, most items will have decomposed down to carbon dioxide, water and sludge within two years, triggered by sunlight, air and water.

The biodegradable materials and products thus created feature a clear “recycle-by” date that shows consumers they have a specific timeframe within which to dispose of the products in the recycling system before they start breaking down. This approach is, of course, dependent on there bing ways of responsibly disposing of plastic waste – including recycling and reusing in a circular economy.

The interesting thing about this PAS is that it’s more than just a specific measurement. It’s introducing a whole mindset about specificity, timing and measurability to the usual compostability and biodegradability narrative. Niall Dunn, Polymateria chief executive, is reported as saying “We wanted to cut through this eco-classification jungle and take a more optimistic view around inspiring and motivating the consumer to do the right thing. We now have a base to substantiate any claims that are being made and to create a new area of credibility around the whole biodegradable space.”

Standards as constraints

-

For any innovative company trying to launch the ingredients for new, biodegradable materials and products, it can be difficult to gain the traction essential to engage with the big guys in the world of legacy plastics. The technical staff at most of their potential customers have an automatic, knee-jerk reaction – “does it comply?” and/ or “can you document it?”

Such reactions make it very difficult for innovative companies that are “ahead of the game” and in unknown, uncharted technical territory where there aren’t yet any agreed standards. Unfortunately, the emergence of new technical standards usually involves industry-wide consultations and long, complicated gestation periods. Startups and market entrants often only have limited resources, and it can therefore be difficult to “make the leap”. One result of these constraints is that old-school thinking can delay and hinder the introduction of transformational business models and technologies that might help redress or repair planetary-scope ills.

One way to break such log jams involves leading by example, which seems to be what Polymateria has done. However, this requires a “mega” mindset that appreciates the bigger, transformational issues and opportunities. Many of the bioplastics companies aiming for long-term commercial breakthroughs have understood this, and their marketing reflects the need to establish new strategic narratives, rather than traditional standards-compliance chasing.

Part of bigger agendas – “zero waste”

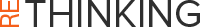

Once the technical experts get warmed up, the whole biodegradability discussion easily ends up hogging the limelight in discussions about recyclability and circularity. However, it’s worth remembering that biodegradability is itself only a small part of a much larger and more comprehensive discussion about how society deals with waste of all kinds, and the mindset involved in rethinking these century-old disposal habits.

From different perspectives, this can be seen as a whole-life or a zero-waste approach, involving rigorously defined steps to move away from the linear use of materials to a comprehensive, compulsory circularity in the future.

Zero Waste is a philosophy that encourages the active redesign of resource life cycles so that all products are reused. The goal is to completely do away with any waste being sent to landfills, incinerators or the ocean. The process recommended is essentially similar to the way resources are reused in nature. For example, the definition adopted by the Zero Waste International Alliance is:

The conservation of all resources by means of responsible production, consumption, reuse, and recovery of all products, packaging, and materials, without burning them, and without discharges to land, water, or air that threaten the environment or human health

Wouldn’t that be wonderful?